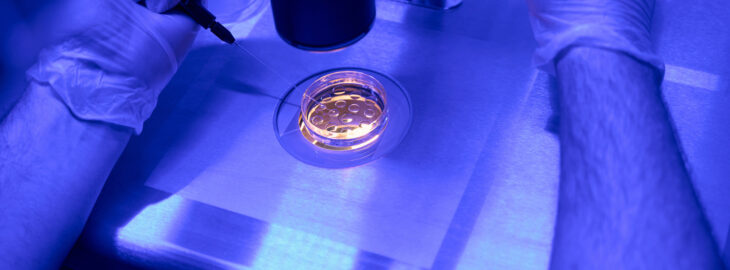

The rule that human embryos cannot be cultured in the lab for more than two weeks should be extended to 28 days, according to experts.

The 14-day limit is the length of time that a human embryo can be developed in vitro for scientific research according to laws in countries including Spain, the UK and Australia.

However, evidence presented at the annual conference of UK-based charity Progress Educational Trust (PET) suggests there is no moral reason for policymakers not to revise their rules.

The aim of the annual conference of the Progress Educational Trust (PET) was to provide an update on fertility, embryo, and surrogacy law in the UK and elsewhere, and to debate what and how much change is needed.

A session sponsored by ESHRE explored what is happening in fertility law across Europe from a perspective of current challenges and changes.

In his presentation, Hafez Ismaili M’hamdi explained the rationale for a recommendation last month by the Health Council of the Netherlands to double the country’s 14-day embryo culture limit. Stem-cell-based embryo models were included in the Council’s decision to extend the limit additional to the surplus embryos donated from IVF patients.

Dr M’hamdi, who is vice chair of the Dutch Centre for Ethics and Health, said the expert committee that advised the Council attempted to balance the rights of the embryo with scientific advancement.

The guidance was based on intrinsic and extrinsic considerations such as those for the embryo’s own sake, the embryo’s symbolic value, and societal acceptance of active use of embryos. Some believe that an embryo should have moral status but this argument fell away because embryos are not sentient, said Dr M’hamdi.

The committee acknowledged that ‘it is impossible’ to pinpoint when embryo culture for research purposes becomes no longer morally acceptable. Despite this, the members said an important reason for their conclusion was that scientists should be allowed to study embryos up to 28 days for the benefit to society such as the prevention of developmental disorders.

Whether the Dutch government reforms the Embryo Act remains to be seen although the ministry for Health, Welfare and Sport commissioned the review.

ESHRE’s recent good practice recommendations on add-ons in ART were the focus of a presentation by Anja Bisgaard Pinborg who participated in the working group. Use of these optional treatments is growing yet they are largely unproven: most of the 27 add-ons examined by the ESHRE committee were not recommended for routine clinical practice.

Public funding could minimise add-ons uptake according to Professor Pinborg from the University of Copenhagen. Data show that the number of fresh ART cycles undertaken by patients decreases when they have to pay which was the case in Denmark when the government withdrew funding for a year in 2010.

Are societies such as ESHRE attempting to stifle innovation? No, said Professor Pinborg who pointed out that the extra cost of a treatment add-on may reduce the number of ART cycles that people can afford overall. The consequence of this may be a decrease in desired family size.

Donor conception and anonymity is a hot topic and presents unique challenges in different European health systems.

Kirsten Tryde Macklon presented insights from Denmark where donation was anonymous until 2012 and is still allowed (but not surrogacy). This policy said Dr Tryde Macklon is ‘a thing of the past’ on the basis that donor-conceived children can now find their biological relatives for example on genealogy websites.

Attitudes among sperm donors have changed too. Dr Tryde Macklon, who is head of Fertility Preservation at Rigshospitalet, said that from information she received from a sperm bank, 60% of their donors are not anonymous whereas in the past most young men did not want to reveal their identity.

Discrepancies do exist between what sperm donors are allowed to know about their offspring and what can be disclosed to egg donors. In the case of sperm donors, they cannot be told if their donation has led to the birth of a child. But women can call the clinic a year after they donate to ask for information about any offspring born from their donation.

Another issue highlighted by Dr Tryde Macklon concerns how many families a sperm donor can assist. In Denmark, the maximum is 12 but local laws do not apply internationally which means what goes on outside Denmark cannot be monitored by Danish organisations.

A key take-home message from this PET conference is that – as society and science move on – change is required to provide patients with the best support.

This may be politically and ethically challenging and must still ensure people seeking ART, gamete donors and those born from fertility treatment are protected from harm.

But policymakers and clinicians need to adapt to fast-paced societal changes and scientific advances, and rules governing the fertility sector are only of value if they are fit for purpose.

You have to be logged in and an ESHRE member in order to comment.